Article taken from The Atlantic

Is the company destroying full-time work, entrenching us in part-time purgatory, or empowering America’s most independent workers?

In the last few years, Uber has gone through a life cycle that once took successful companies decades to complete—from start-up to upstart, from pushy disruptor to pushy behemoth, from iPhone button to cultural icon. Uber’s executives don’t like to associate themselves with the “sharing economy,” the smattering of firms that allow average Joes to sell access to their fallow goods and services (rent my empty home on Airbnb, buy my open 3 p.m. hour on TaskRabbit). The company’s ambitions, it says, are grander. But for now, the vast majority of drivers are behind the wheel of their own car. “Sharing” is, to be quite literal, the majority business of Uber.

This puts Uber squarely in the crosshairs of a debate about what exactly this peer-to-peer economy means for the future of the economy. (Like all discussions that include the term “future of the economy,” this can amount to little more than rounding up some very recent developments and projecting forward 10 years with jaunty confidence.) Are these new companies creating value from nothing, or destroying the value of the formal economy? Are they inventing new, flexible ways for underemployed Americans to work, or are they contributing to the destruction of full-time jobs?

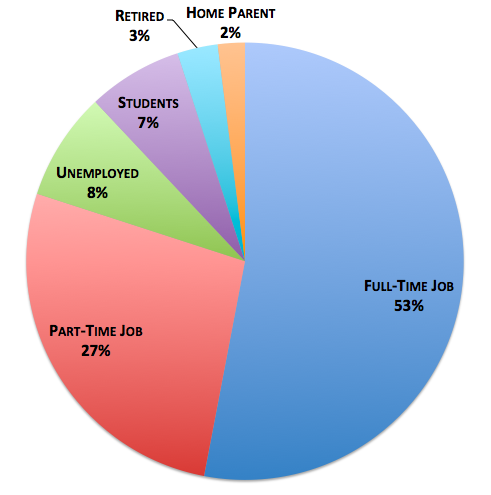

The typical Uber driver is a college-educated man, married with kids, who is supplementing a full- or part-time job with about 15 hours of driving a week, logging 20 to 30 trips, and earning an extra $300 to $400 a week (before factoring in the cost of gas and upkeep). That’s according to a new paper by Alan Krueger, the eminent Princeton economist who served as chairman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, working with Uber’s head of policy research, Jonathan Hall. Krueger and Hall based their research on both Uber’s data and an online survey of 600 Uber drivers in 20 markets, including New York, Washington, and San Francisco.

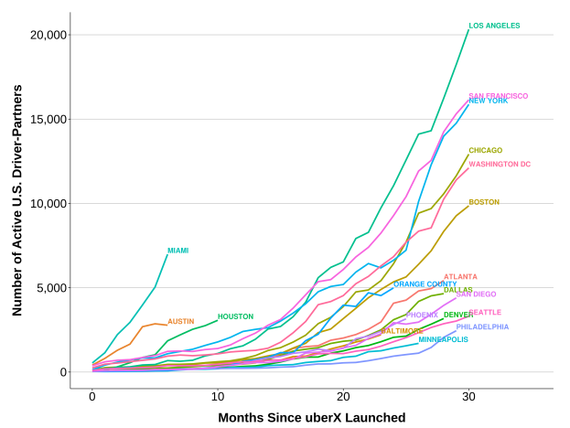

The best way to review the paper’s factoids is to flip through the pretty pictures. Uber’s growth exploded in late 2013 thanks to the rise of its cheaper uberX program, which now accounts for more than 80 percent of its drivers. The largest market of uberX drivers is Los Angeles. The fastest-growing are new entrants Miami and Austin.

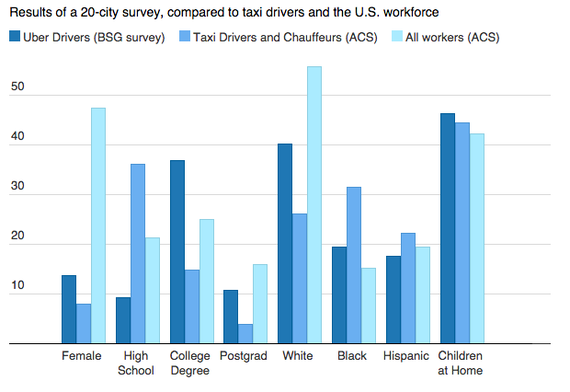

According to the online survey, Uber drivers are almost 90 percent men, which is still more female-heavy than taxi drivers. They’re also more diverse (defined as: less white) and more college-educated than the general workforce, but similar in age and likelihood to have a kid. In other words, Uber drivers are a fairly perfect representative sample of a typical U.S. metro area workforce.

Wife, Kids, and a B.A.: The Uber Driver Demographic

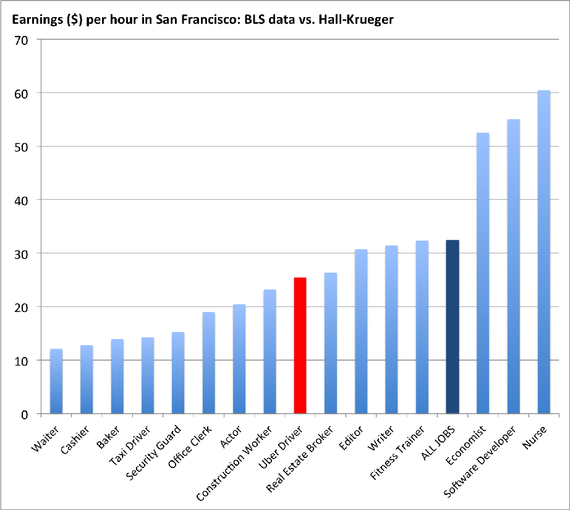

In large cities, uberX drivers report earning between $15 (Chicago) and $25 (San Francisco) per hour before factoring in the cost of gas. How does that stack up against other jobs?

To give you a rough, rough sense—really, I can’t stress enough the roughness of the sense, since I’m comparing figures from separate surveys and not including driving costs—I’ve graphed a comparison of self-reported hourly earnings of Uber drivers in San Francisco against the hourly earnings of other San Francisco occupations from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ occupational employment stats. At least in this comparison (rough!), driving with Uber is a more efficient way to make money than the most common jobs in America, cashiers and retail salespeople, or being a taxi driver, a baker, or a construction worker. It’s still not as lucrative as the average San Francisco occupation.

How Much Can You Make Driving Uber?

Before Uber: 80 Percent Working Full- or Part-Time Jobs

DEREK THOMPSON is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he writes about economics, technology, and the media. He is the author of Hit Makersand the host of the podcast Crazy/Genius.